The history of coffee is a long one. From it’s speculated origins from an Ethiopian king, a petitioned ban in 1674, the historical beliefs it caused blindness and bad grades, and it’s blame in the 1960’s for high blood pressure, coffee today is hailed as a drink with a variety of health benefits.

The history of coffee is a long one. From it’s speculated origins from an Ethiopian king, a petitioned ban in 1674, the historical beliefs it caused blindness and bad grades, and it’s blame in the 1960’s for high blood pressure, coffee today is hailed as a drink with a variety of health benefits.

Recently, coffee lovers have cheered a series of studies showing the brew’s positive health impacts, including its ability to reduce heart attacks and lower chances of certain types of cancer. The latest good news came in November: Astudy led by Harvard researchers found that people who drink three to five cups of coffee a day have a 15% lower risk of death.

But the apparent consensus that coffee is good for you — or, at least, isn’t bad for you — comes after centuries of confusion.

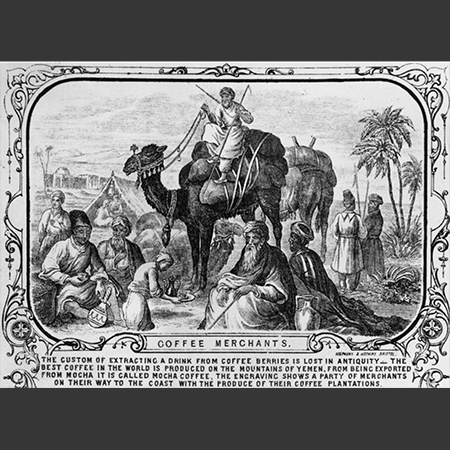

The origins of coffee aren’t entirely clear, but one legend says a young Ethiopian goatherd named Kaldi noticed his flock goinghappily berserk after eating the fruits of a coffee plant. He tried it, liked it, and by the 1500s the resulting brew had spawned coffeehouses across the Middle East — where the first known health concerns arose.

After determining thatcoffee led to gambling and “criminally unorthodox sexual situations,” the ruler of Mecca ordered coffee houses closed in 1511. Some historians believe the ruler, Khair-Beg, shut them down for political reasons, though, and the policy was soon overturned anyway.

After coffee traveled to Europe in the late 1500s and became linked to intellectual pursuits there, chemists and physiologists — themselves part of a new age in scientific advances — began to study coffee’s effects through controlled experiments, often on animals. They generally trumpeted its positive effects, saying it could cure headaches, boost digestion and sharpen focus. (Coffee appeared in medical texts, the Materia Medica and Codex Medicus, until the 20th century, largely because doctors considered it a drug more than a drink.)

In one text from the 1600s, a doctor recommends that people with “cold, heavy Constitutions” spend time in coffeehouses to cure headaches and fever. (The text advises against this solution for those with “hot” and “lean” constitutions “because it may dispose the Body to inquietudes.”)

Around the same time, doctors in England began prescribing coffee as a cure for alcoholism, or, at least, a replacement for alcohol. But a group of women believed coffee was making their husbands impotent, so they filed a petition to ban coffee in 1674.

“The fame in our Apprehensions can consist in nothing more than the brisk Activity of our men, who in former Ages were justly esteemed the Ablest Performers in Christendome,” the women wrote. “But to our unspeakable Grief, we find of late a very sensible Decay of that true Old English Vigor.”

Over the next three centuries, researchers battled it out over coffee’s benefits, and by the 1920s studies had suggested drinking coffee could cause blindness, stunt growth, trigger anxiety, stoke heart palpitations and even result in bad grades.

But the real concern started amping up in the 1960s and ’70s when a series of studies, published in reputable journals, linked coffee to heart attacks, high blood pressure and strokes. Doctors advised cutting down on coffee or even nixing it altogether.

Until recently. Starting in the mid-2000s, researchers began doing analyses of coffee-related studies, looking at the larger body of research over time. These analyses emphasized studies that were able to isolate coffee’s effects, rather than the studies where other factors, like smoking or obesity, might have impacted the outcome.

Now, a series of these meta-analyses, have concluded that, not only does coffee not cause heart attacks or strokes, it’s actually good for you in moderate amounts, thanks to high levels of antioxidants. Research has found it cuts the chances of liver cancer, diabetes and Parkinson’s, and promotes a healthy heart.

Earlier this year, dieticians suggested that official US dietary guidelines recommend drinking three to five cups a day, making it the first time the government could actually push coffee drinking.

The latest good news, published in the journal Circulation, found that non-smokers who drank three to five cups a day — considered a “moderate” amount — had a 15 percent lower chance of dying from heart disease, stroke, diabetes, neurological diseases and suicide. (Those who drank one to three cups had an 8% lowered chance.)